Lime putty for mortar has been in known use for over 6000 years. Modern Portland cement, lime and sand mortars have dominated for less than 100 years with many known failures. Here are what some modern scientific investigations have found about what worked so well about lime mortars and why so many modern mortars may not be appropriate for historic restoration. This information is offered so that you can make an informed choice on which binder to use for your projects.

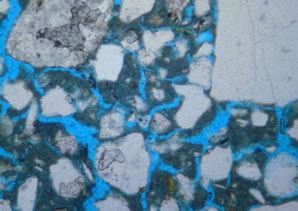

1 LIME PUTTY TO 3 PARTS OF SHARP SAND

This cross section cut away of a traditional lime putty mortar demonstrates via the blue dyed epoxy resin, which fills the open pore structure, that historic mortar based solely on lime and sand have a tremendously high and desirable liquid and vapor permeability.

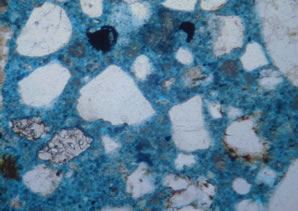

1 NATURAL HYDRAULIC LIME (3.5) TO 3 SHARP SAND

Note the high porosity of this mortar formulation. The wall can breathe by allowing moisture to enter and exit the system, encourage the crystalline bridging phenomenon (also known as the autogenous or self-healing properties of lime mortar) by dissolving free lime in the mix and re-depositing it to close larger fissures. Excess moisture then quickly evaporates back into the atmosphere. The open pore structure allows the carbon dioxide, needed for carbonation during curing, to be delivered deeper into the mortar.

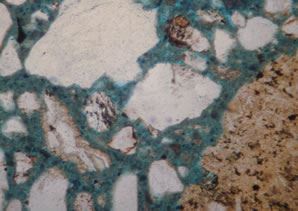

1 NATURAL HYDRAULIC LIME (5) TO 3 SHARP SAND

Note that the pore structure is still open but finer and more dense than the Natural hydraulic lime 3.5. This mortar is suitable for copings, parging and pointing in extremely wet conditions including sea driven rain with high salt content.

1 PORTLAND CEMENT TO 3 PARTS SHARP SAND

Note the dense fabric and the greatly reduced porosity, with only the presence of shrinkage cracks. The shrinkage cracks are a portal for moisture to get into the absorptive bedding mortar (usually of lime and sand.) Normally, the sun will draw moisture back out of a lime joint. However, Portland cement based mortars trap moisture within the wall system because their dense pore structure does not always allow it to escape through evaporation. The saturated wall of trapped moisture can lead to moisture being driven much further into the building when heat inside draws moisture through the wall, or trapped moisture evaporates out through the softer historic brick or stone accelerating its deterioration.

Petrographic thin section images courtesy of William Revie of The Construction Materials Consulting Group; Stirling, Scotland

Presented by LimeWorks.us

Phone: 215-536-6706